In December, 2025, my wife Karin and I took a cruise in southwest Africa, terminating in Cape Town and then went to Zimbabwe for wildlife viewing. What started as notes for my annual holiday letter to friends took on a life of its own, and I’ve been sharing this larger than expected work already. As a forewarning, some of this is a conventional travelog from a personal perspective, but much is personal anecdotes that can’t be replicated but are of the sort that can happen when you travel and that make it fascinating.

Cape Town is wonderful

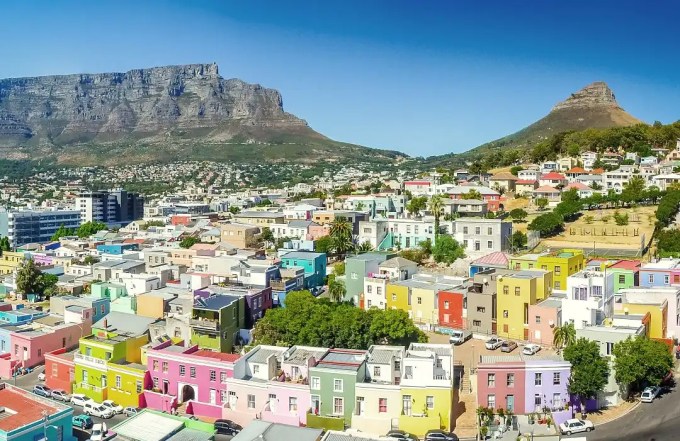

Our December 2025 West African cruise put us in Cape Town, one of our very favorite cities, for the third time in 12 months – all being the terminus of cruises. For those unaware, like our home town of San Francisco, Cape Town has a multicultural population, temperate weather, a foodie culture and nearby vineyards with great wineries and tasting rooms. And while Robben Island doesn’t have the pizzazz of Alcatraz, for 27 years it incarcerated Nelson Mandela, whose inspirational story can be learned there. The city also has the breathtaking backdrop of Table Mountain (where thick clouds can flow down from the flat top like waterfalls) plus Signal Peak and the 12 Apostles. With that, it completes the list of the world’s four most stunning combined urban/mountain/seascapes along with San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Rio. Cape Town has a visual sparkle and lifestyle zeitgeist that competes with Sydney; beautiful, white-sand beach town suburbs like Miami; botanical gardens and bird sanctuary (both with many species unique to the area) akin to Singapore; remnants of colonial history and architecture; and probably the best pan-African artisan and arts markets anywhere. Oh, and there are national wildlife reserves within a few hours drive endowed with lions, elephants, and such. Other than that, Cape Town is quite ordinary.

This time we visited the Zeitz Museum of Modern African Art on the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront – that’s not a typo – the city honors her son who visited there, not her husband Prince Albert. The spectacular interior of the edifice was carved from a battery of adjoined cement grain silos. Its 60-foot-high atrium reveals various oval cuts and abutments sliced from the original silos, and this magnificent centerpiece alone is worth the price of admission.

Ice and imitation

Our other notable experience in Cape Town in 2025 started in 2003, when we entered its most distinguished diamond retailer – Prins & Prins. After being seated, the salesman, noting the dulled 2 ½ karat sparkler on Karin’s finger, asked “May I replace your cubic zirconium?” Surprised at his observation and presumptuousness at its not being a diamond, she replied “What would it cost?” “No charge,” said he. This is a diamond merchant, replacing a CZ for free on his own initiative. Are you kidding?

Flash forward to December 2024, and we return to Prins & Prins and have the seemingly dulled, free CZ from 2003 replaced for the modest cost of labor. Karin was never that happy with the new one and when we knew we would be back in December 2025, we scheduled an appointment for yet another replacement. They set aside two possible successors, and as a courtesy when we arrived, buffed up the old 2003 rock that Karin had, of course, saved and brought along. Of the four possibilities, the 2003 CZ that they initially gave her looked the brightest and biggest, and lo and behold, it is back in the setting again (you may age yourself if you thought of Gene Autry’s song “Back in the saddle again”).

Prins and Prins paid 75 cents for this promotion. Not really, but they did give us free bottled drinks along with all of their attention. It still amazes how well they treat us, time-after-time, pretty sure that we’re not going to spring for $45,000 to buy the real thing.

Benin – fond memories from one of the world’s poorest countries

Our cruise embarked in Accra, Ghana, but since we had been there before and since Ghana’s new visa process is extremely taxing and threatening, we decided to skip it and strongly recommend that others avoid Ghana as well. Karin detailed the process to her orthopedist, who is African-American and had planned a one-week slave-history related vacation to Ghana with his family of four, and he abruptly cancelled.

Our southwest Africa cruise actually began in Cotonou, Benin, the commercial center of the country near the capital of Porto Novo, but it almost didn’t, as there was a failed coup two days before we left SFO. We didn’t know if we might get stuck in Paris (there are worse places to spend a few unplanned days), or worse yet, if we would get to Benin and our cruise ship would decide to bypass the destination because of the risk. The cheapest way to get out of Benin and make it to a later destination on the cruise would have been to return to Paris and then go to Lisbon! As it turned out, Cotonou’s airport and seaport were reopened and we made it.

On the flight from Paris, we had met a young Beninese man who works for Google and lives in the Bay Area. After we returned home, we found that he and his wife both had to make unplanned trans-Atlantic flights concerning her residency to deal with Trump’s scheduled travel ban, instituted with his characteristic racism, ignorance, and lack of any cohesive plan. Ash showed us around town in a way that only a local could, insisting on paying for everything, including a restaurant that no tourist would find, so it turned into a great visit.

Highlights of Cotonou were the longest graffiti mural in Africa, at over 3,000 feet, along a main artery, with many artists contributing panels to the appealing attraction; the vast open market with hundreds of mostly grocery and fabric stalls; an exurb of 40,000 people all in houses on stilts in a lake that is only accessible by water; and seeing the hoopla surrounding a woman who had already broken the Guiness Book of World Records standard for continuous cooking – though she was allowed, by Guiness rules, two hours sleep per night and 15-minute breaks every four hours. She was in her 11th day and targeted 14 to smash the world record of six days. Taking advantage of the buzz, 60 or so temporary food, tchotchke, and entertainment kiosks sprung up near the Convention Center, creating a carnival-like atmosphere. Despite the level of poverty in Benin, our hotel was among the more lavish that we’ve stayed in, with huge grounds.

What a difference a fly makes – Another song reference, this from Dinah Washington, substituting fly for day, which also works for the story

The greatest trepidation on this trip because of long term or terminal implications came from São Tomé and Principe, a tropical island nation that is Africa’s smallest country. I was bitten on the elbow by what we are certain was a tsetse fly, which causes African sleeping sickness, a usually fatal disease, though treatable if caught in time. Karin and I both saw the bite occur from the fly, which is several times larger than a common house fly. It left pain, itch, and a 1 ½ inch in diameter round, red spot. Other than the Crystal Cruise doctor, who was not a tropical disease specialist and had no available treatment, I was unable to get medical attention until four days later in Namib, Angola.

With the help of the driver of a Crystal contractor, we had an adventure searching out five different pharmacies looking for medicine. Many travelers would find this a real headache, but we enjoyed having a mission, interacting with the locals, and seeing the town beyond the touristy spots and things to do. The reason for lack of availability of medication was that the northern Angolan jungle is endemic with sleeping sickness, but Namib is in the desert, with no incidence of tsetse flies. Finally, someone recommended going to a hospital. The hospital was free, and I was whisked through the emergency room and attended immediately. The knowledgeable doctor noted that since I didn’t have site infection within three days, I was likely clear, but that I should look for symptoms over the next few weeks. It seems that I dodged the bullet on that one.

Safari – our main, but not only, motivation for African travel

The trip ended in Zimbabwe and Botswana with great land photo safaris (Hwange in Zim and Chobe in Botswana) with great guides as well as wonderful safari cruises on the Zambezi and Chobe Rivers. It doesn’t appear that canoe rides near Victoria Falls among the hippos and crocs like we took in 2002 are allowed any longer because of danger. Except for ubiquitous impalas, elephants, hippos, and crocs, wildlife sightings on land were relatively low because rainy season provides cover and well distributed water, so that game doesn’t have to go to permanent water holes. We did see zebras, wildebeests, jackals, kudu, water bucks, warthogs, buffaloes, striped mongeese, steenboks, and more – including rare and beautiful painted dogs although in an acres large jungle reserve. But a wide variety of interesting birds is always around, and the wildlife and whole experience was still amazing. Hwange is elephant rich, and we had two or three very close and threatening interactions with elees. A first for us was that our safari vehicle was able to follow two brother lions cavorting and marking their territory repeatedly.

By the way, the Zimbabwe city of Victoria Falls, which was our hub, is unique for multinational game viewing – strongly recommended. Within two hour drives or less, you have your choice of wildlife in Zim, Zam (Zambia), Botswana, and Namibia. There is even a nearby bridge that touches all four countries. Plus, there is the falls – the largest continuous sheet of water in the world. Iguazu has more total water flow but is broken into many divided cataracts. Niagara is the third in size in this unique group of massive cataract waterfalls, but still spectacular.

Despite the appeal of a Vic Falls based itinerary though, for first-time safari goers, South Africa offers the most. While Kenya and Tanzania attract more attention, they target foreigners exclusively and are priced accordingly, while South Africa has its own large middle class and includes game options that are targeted for them as well as the well-heeled. And for supplemental activities, it is without peer.

Huge stress to make the plane

Our 40-hour door-to-door return home (longest ever for us) started with a time-pressured, white-knuckle, two-hour drive from a remote camp in Zim’s Hwange National Park on a heavily potholed, muddied, puddled, dirt road on which we saw no other vehicle for over an hour. Oh, yes, and we had already blown out a tire the previous day, and couldn’t get a replacement in this isolated area, so if we’d had another flat, we would have been marooned without a spare for a good while and would have missed our three-flight program home. We made it to the airport with minutes to spare, but understandably had to pay extra fees to the car rental company for tire replacement, minor damages, and cleaning the mud-covered car.

Anecdotes for the informationally curious

As a side note, all of you probably already knew that Angelina Jolie birthed her twins in Swakopmund, Namibia (or maybe not!), and that this town of mild climate has virtually the same monthly average temperatures (reversed for different hemispheres) as Monterey, California, both benefiting from cold currents from their respective polar oceans. Also, nearby Walvis Bay (another stop on the cruise) has the longest palm tree alley in the world with 1,800 mature trees spread over three miles on the highway toward nearby Swakopmund.

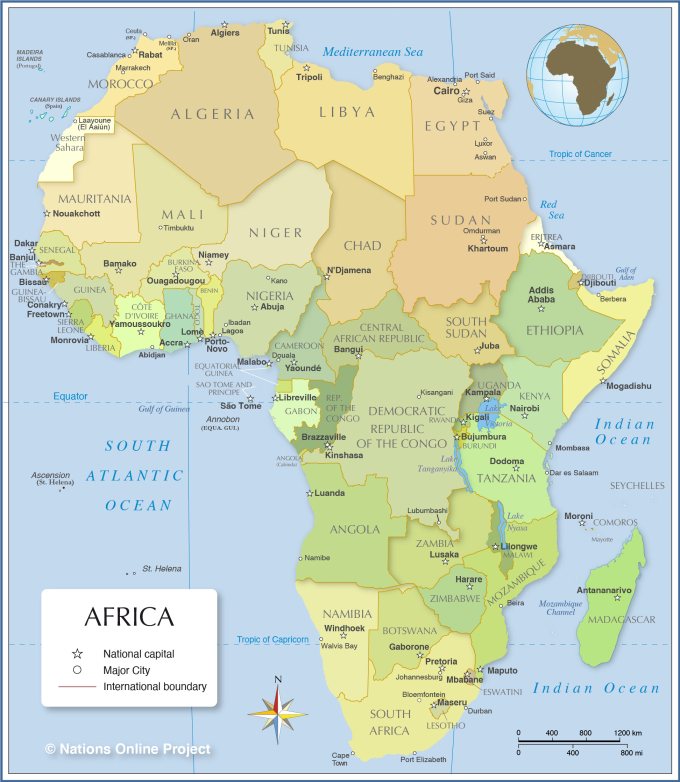

Confusion from naming abounds in this region, largely thanks to colonial rule. It has the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with their national capitals across the street from one another. The city of Namib is not Namibia, but Angola. Benin City is not in Benin, but in Nigeria. And the famous Benin bronze statues are from Nigeria, not Benin. Former colonies along the Bight of Benin (the country was named after the huge gulf, not the reverse) were originally and oh so cleverly named Gold Coast, Grain Coast, Slave Coast, while only Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire in the official French) persists with the colonial name as the country name.

Finally, Americans tend to look at slavery from a U.S. perspective, and we view the main sources of slavery as being Gambia (“Roots” and Alex Haley’s ancestral history started there) and Senegal (President Obama visited Gorée Island, off Dakar, with its “Door of No Return”). But, get this, present-day Angola provided more than 10 times as many slaves to the Western Hemisphere than the combined other two mentioned. Who knew?