Robot, replicant, android, or body snatcher – one of science-fiction’s leading obsessions has long been the fear of alien or man-made “beings” replacing humans. In playwright David Templeton’s “Galatea,” the near future envisions an outer-space centered universe populated by organics, like you (I think) and me, as well as synthetics, the latter being created by the former to appear and behave exactly like humans.

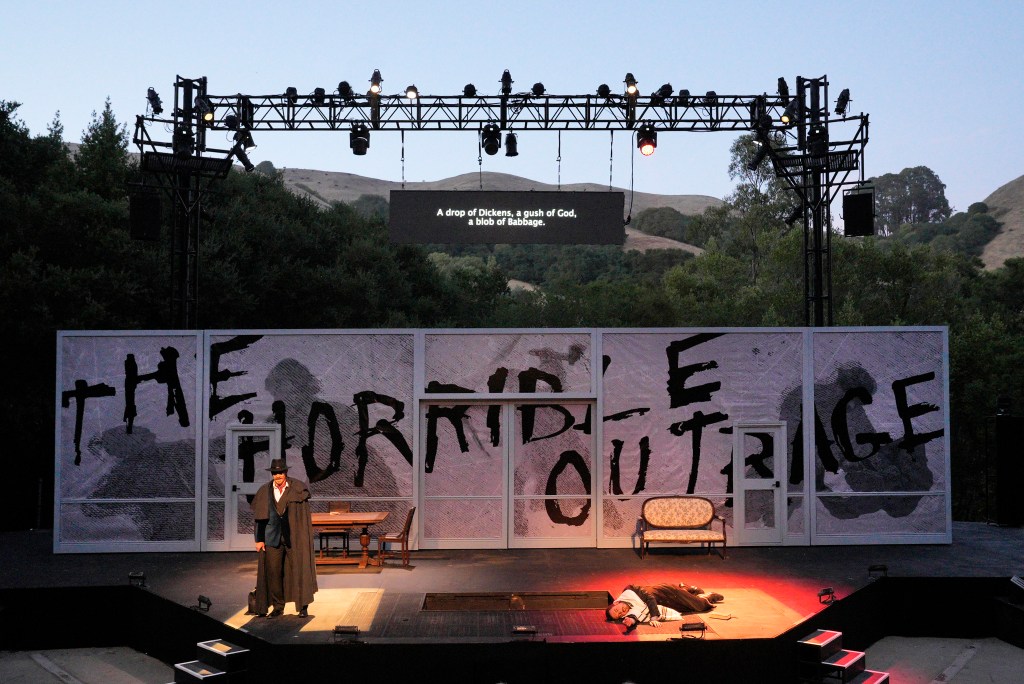

This Spreckels Theatre Company production was scheduled for its world premiere last spring when the pandemic hit and delayed its opening until now. The wait for the delightful dramedy was well worth it. Rather than striking Elizabeth Bazzano and Eddy Hansen’s striking set, the stage remained ready for its opening 18 months later. The script itself benefitted from a distinctive fate as well. The Glickman Award is granted to the play and playwright voted the best premiere for the year in the Bay Area. Past recipients include Tony Kushner, Sarah Ruhl, Marcus Gardley, Lauren Yee, and a laundry list of other respected authors. Though “Galatea” was not eligible in 2020 because the production never launched, it received an unprecedented Honorable Mention from the voting committee.

The central plot concerns the only known survivor from the colony vessel Galatea, the synthetic Seventy-One, who was found in space after spending 87 years in a cryogenic evacuation vehicle. Therapist Dr. Margaret Mailer is assigned to debrief and acclimate her to the new environment. The action takes place completely on a space station in Mailer’s office, an eclectic mix of contemporary furnishings with Asian artifacts; tin roof sheets cleverly lit to look like columns of shiny poles; and a large Palladian window casing that she is particularly proud of.

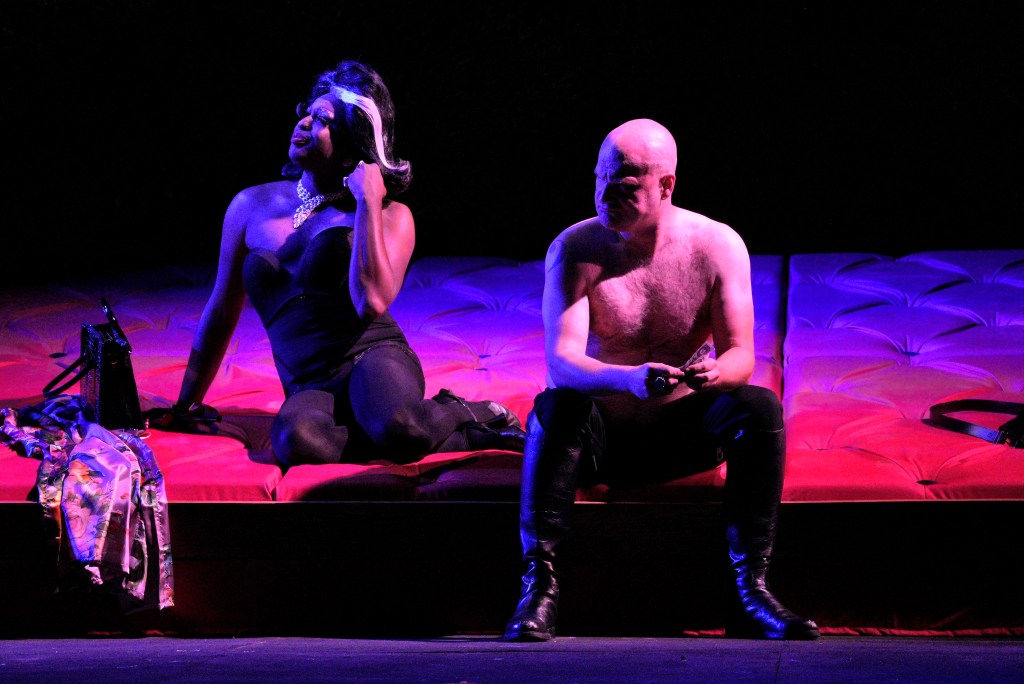

The cast is led by the spectacular Sindu Singh as Dr. Mailer. With a crisp Anglo-Indian accent, a quick wit, and a faster laugh, her occasional humorous f-bombs followed by abject apologies for her language seem out of character at first, but after all, we’re not in Kansas anymore. Singh is absolutely confident, convincing, and compelling as she teaches Seventy-One common human behaviors like shaking hands and coordinating body with verbal language. All the while, she tries to plumb Seventy-One’s lost memory to solve the mysteries. What, if anything, happened to Galatea, other than the known loss of its communication signal? Was Seventy-One involved in its disappearance or destruction? How and why did she evacuate, and was she the only one? What is she holding back?

Meanwhile, after nearly a century in the deep freeze, Seventy-One is out of touch and out of date. Technology for synthetics has improved immensely, so that current models are totally human-like. Played to great effect by Abbey Lee, Seventy-One is virtually opposite to Dr. Mailer – austere, abrupt, and robotic in movement. When taught to look more humanlike, her efforts are mechanical – a strident hand shake and a square-mouth, rigid smile. But worse, she is overcome with anxieties. Although she remembers all of the technical details of the Galatea and her work on it, she resists remembering her personal past, fearful that after whatever revelations she provides, she will be destroyed by the organics.

Apart from the comedy and mystery of “Galatea,” it operates as a cautionary tale. Earth will always survive. Life on earth may not, and the greatest danger to life is human hubris. We procreate with impunity, resulting in exponential increases in population, and devour resources at increasing per capita rates, a formula that will inevitably result in dire consequences. Then we use our intelligence to find solutions to the problems we created, which often have greater negative unintended consequences. And with regard to synthetics as a solution, one human feature that can’t be replicated is the ability to reproduce organically. If they replace life forms, will they have the ability to design their own replacements? Will they even care? What will motivate their continued existence? Would we care?

I should note that there is much more that is interesting to share, but I’d rather not ruin the sense of discovery for readers who might attend. Kudos to director Marty Pistone for not giving up on this project despite the delay and to additional cast members Chris Schloemp and David L. Yen who also do fine work. With a total drive time during normal conditions of 2 ½ hours, Spreckels is usually outside my range for attending theater. Making an exception for “Galatea” paid off. It entertains and provokes and offers some surprises along the way.

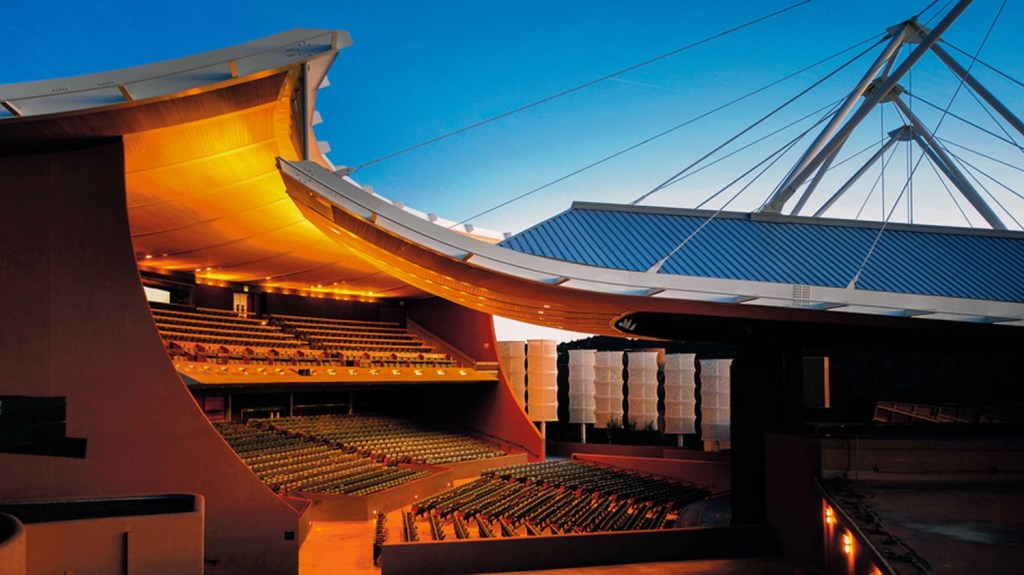

“Galatea” is written by David Templeton, produced by Spreckels Theatre Company and plays at the Spreckels Performing Arts Center, 5409 Snyder Lane, Rohnert Park, CA through September 19, 2021.

Victor Cordell

San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Critics Circle

American Theatre Critics Association